Stretchability in a brand, 1988

- Date: 1988

- Publisher: Marketing

- BRANDS

A column in Marketing about just how far a brand can be stretched without diluting the value of the original drew a letter of complaint from the CEO of Jockey, one of the classic generic brands – and an offer of new underwear.

Stretchability in a brand

There is also the possibility that M&S, which has had shaky success in North America so far, will nudge its own products into Brooks Brothers stores” – The Times May 3, 1988.

“Good morning, sir. May I help you?”

“Thank you. I would like one button-down cotton oxford, size 15.5/33, in the solid blue; one pair of cordovan loafers, size 8E; and two cod and prawn fishcakes suitable for the microwave.”

“With pleasure, sir. Charge or cash?”

Just how far a brand reputation can be stretched without diluting the value of the original is one of the constantly fascinating debates in marketing. Cadbury’s must have thought hard before it lent its name to milk powder; and even harder before it went into instant mashed potato. Mars is surely right to use Pedigree for its pet foods. I haven’t yet got used to Prudimgential as an estate agent.

Dunhill was clever to recognise that a reputation for classy cigarettes and lighters could be extended beyond smoking into classiness generally. It was more logical to go from tobacco to tailoring than it would have been to launch a Dunhill roll-your-own.

Parker Pen agonised for years before the ballpoint

Retailers’ names have far greater elasticity than manufacturers’: presumably because their skill is known to lie in selection rather than in making. Wilkinson Sword could go from secateurs to razor blades to (just) shaving cream. But not, I think, to after-shave to eau-de-toilette to challenging Poison. Harrods could, and do, stock the lot – and so could Boots.

Many people are so acutely conscious of the risks involved in attempts to (as we say in marketing) optimise a brand franchise that timidity sets in. Parker Pen, at least in this country, agonised for some years before deciding to market a ballpoint; and even then it was called not a ballpoint but a ballpen to distinguish it (a subtlety lost on the public) from the Bics and the Biros. Parker’s hesitation was prudent. All ballpoints at the time were cheap, plastic and disposable; and Parker was selling not writing instruments but expensive and lasting gifts. Until recently, cheques signed with anything other than a fountain-pen had been invalid. In the event, it was in part the authority of the Parker name that brought respectability to the entire category.

Playing a game called Brandicide

The best way I know to overcome such timidity is to play a game christened, if not invented, by Doug Richardson. It’s called Brandicide and its nature is so self-evident that I’ll explain it to you.

Take any powerful brand – and mentally extend its name to a new venture of such a kind that the parent’s brand values are killed outright. It’s not as easy as it seems. After Eight Chewing Gum seems a likely starter; but on reflection, the Parker effect might come into play and legitimise the sector; and adult sophisticated chewing gum is not an impossibility. But After Eight Bubble Gum is another matter. Brandicide has been committed.

The piece in The Times, for an instant, conjured up the vision of a double death – like two duellists killing each other simultaneously. Mariner’s Bake and Madison Avenue: the immediate extinction of both Brooks Brothers and St Michael. But I expect that all they had in mind was Y-Fronts.

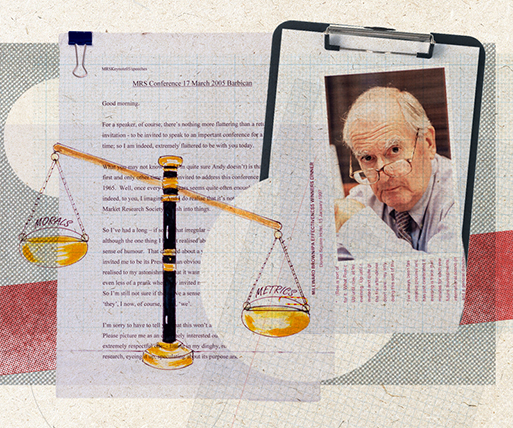

Courtaulds Clothing Brands (Jockey) CEO L J Walker to Jeremy Bullmore

10 June 1988

Dear Mr Bullmore,

As a Brand Marketer, perhaps you’ll forgive me for correcting your final point in the piece in Marketing about brand stretchability. Marks and Spencer would not have Y-Front in mind for sale in Brooks Brothers because M&S do not sell Y-Front – it is a brand name which Jockey licence exclusively, ironically from the U.S.A.

It has become one of the classic generic brands to the point where it is even included in the Oxford English Dictionary and eminent marketeers are unaware that it is a brand name!

Incidentally we recently celebrated 50 years of Y-Front in the U.K. Although much improved over time, our garment architecture is essentially the same as in 1988, and if you can get your secretary to let me have your waist size, you can experience why we reckon our Brand is more comfortable and of better quality than its M&S copy.

Yours sincerely,

LJ Walker

Jeremy Bullmore to L.J. Walker

1 July 1988

Dear Mr Walker,

Belated thanks for your letter of 10 June which was sent first to Marketing and only a couple of days ago to me.

I feared as I wrote that I was offending your copyright. The trouble is, of course, that since there’s no alternative generic name, your brand is paid the ultimate compliment of serving two purposes – irritating though it must be at times. So I was well aware that it was a brand name but stumped for another description.

Your final offer is too generous (and forgiving) to resist. My waist size is 34”.

With all best wishes,

Jeremy Bullmore