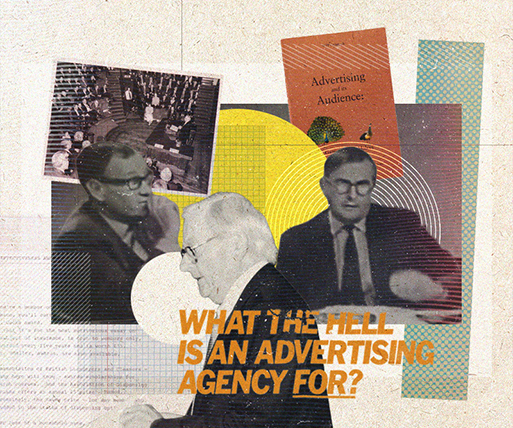

Advertising. What is it? What is it for? 1974

- Date: 1974

- Publisher: Advertising Association

- COMMUNICATIONS

This landmark paper is proof Jeremy has never been just about the ads but rather about the brand and its relationship with consumers. He first pointed out the distinction between advertising and advertisements in a J. Walter Thompson London publication in 1974. He did so again in 1983 when asked to write the introduction to the “Advertising Association Handbook”. The piece contains a pithy definition of advertising that Jeremy revisited in 2015 for the Advertising Association’s “Big Questions” project: “Advertising is any communication, usually paid-for, specifically intended to inform and/or influence one or more people.”

ADVERTISING. WHAT IS IT? WHAT IS IT FOR?

Any discussion of advertising tends to lead swiftly to generalisation. Over the years, I’ve been asked to agree or disagree with a great many different propositions about the business, all of them framed in an extremely general manner. Here are just a few of them:

-

Advertising exploits human inadequacy

-

Advertising is the mainspring of the economy

-

Advertising prevents small, enterprising companies from breaking into established markets

-

Advertising is a force for change

-

Advertising encourages waste

-

Advertising contributes to a more efficient distribution system

-

Advertising puts up prices

-

Advertising puts prices down

-

Advertising disguises the absence of real product differences

-

Advertising encourages product innovation

If all the critical propositions were true, it is hard to understand why advertising should continue to exist – since it would benefit neither producer nor consumer. And if all the favourable propositions were true, it is hard to imagine why any of the critical propositions should continue to enjoy any sort of currency.

The trouble with the statements above, and hundreds more like them, is that they ask us to accept that all advertising has a common purpose and a common effect. The simplest way to expose such a misconception is to take each of these statements and for the singular ‘advertising’ substitute the plural ‘advertisements’. It rapidly becomes evident that each of those statements may be true for some advertisements but none can be true for all.

We use the word advertising very lazily. We use it to mean both the medium and the message; the container and the thing it contained.

In fact, advertising is simply a channel of communication. It’s available, at a price, to everyone; and allows them to make contact with other people for an almost infinite variety of different ends.

Advertisements are the messages that advertising carries in an attempt to achieve those ends. About the only thing they have in common is that they all offer something: an object, a service, a cause, a job or an opinion.

Here are a few of the offers I noticed in a single issue of a recent British Sunday newspaper:

Three development areas, Telford, Birmingham and Swansea. Draught Guinness. British Nuclear Fuels. Castle Coombe Golf Club. ICL, Philips and Digital. The Equitable Life. Independent Financial Advisers. Kall-Kwik printing franchises. An offshore company in Hong Kong for £150 (all credit cards accepted). Are you capable of earning £100,000 pa? Surveillance Equipment (remarkable recording briefcase). Unique Centralised Will Writing. The Royal National Institute for the Blind. Closing down sale of Austrian crystal lighting. Competitive fares from three transatlantic airlines. Irish whiskey. Corporate Health Screening. The BT share offer. The Tobacco Advisory Council (‘Hear the other side’). The Macmillan Nurse Appeal. British Gas. Jobs in teaching from the Department of Education and Science. Nationwide (‘The banks must like small businesses. They’re doing everything they can to keep them that way.’) NatWest (‘The bank more small businesses turn to.’) Opportunities in Kuwait, in specialist coatings and adhesives, as a Creative Food Service Advisor for Travellers Fare, with English Heritage and in chiropody. A Lamborghini for £88,000. Car registration number 1 JAN by direction of the Secretary of State for Transport. Sara Eden Introductions (‘You’ve realised you can’t leave your love life to chance!’). Lalique glass fish on base (illuminated), documented famous last owner, £5,500 ono. Attractive Humorous Swiss female, divorced (38) seeks solvent male for fun and froliks (sic). Vasectomy, one visit. The Royal Opera in Turandot. Balloon flights £95.

Each of these offers was contained in an advertisement, ranging in size from a full page to a couple of lines, and they’re all part of advertising.

The nearest I have ever been able to get to a definition which encompass all advertising’s possible uses and objectives is this inelegant construction: ‘Any paid-for communication overtly intended to inform and/or influence one or more people.’ To take the points in turn:

-

‘Paid-for’. An advertisement that is not paid-for is not an advertisement. The payment is usually to the owner of the medium but even ‘PYO Strawberries Next Left’ carries a cost.

-

‘Communication’. Every advertisement is attempting to bridge the gap between the sender and one or more potential receivers. That bridge is a form of communication. To buy a poster site but leave it blank is not to advertise.

-

‘Overtly’. You may hope to inform and/or persuade others by paying for product placement or public relations advice but it’s in the nature of an advertisement that it can be seen to be one.

-

‘Intended’. Not all advertisements ‘work’ in the sense of achieving their objectives but they’re nonetheless part of advertising.

-

‘Inform and/or influence’. The purely informative advertisement may be rare and it’s anyway notoriously difficult to draw an agreed distinction between information and persuasion; but an advertisement doesn’t have to set out to influence either attitude or behaviour in order to qualify. Some financial advertisements are legal requirements for the record and do not seem anxious even to be read.

-

‘One or more people’. All advertisements are addressed to other people: sometimes one (‘To the man on the M25 on Tuesday at approximately 3 o’clock between J18/19, I'm the lady in the white Escort Cabriolet...'.) and sometimes to millions ('the Community Charge’).

All advertisements have this in common; they want to achieve something and they choose advertising as a means of achieving it. and they all believe, with varying levels of confidence, that they will be better off, in some respect, for having chosen to do so.

The owner of the Lalique glass fish on the illuminated base wanted to identify someone out there who would be interested in paying £5,500 or thereabouts for a Lalique glass fish on an illuminated base. It’s difficult to think how else such an opportunity could have been made widely known. If the offer was taken up and the fish sold, then the last accusation that could be fairly made of that advertisement would be wastefulness. The previous owner was happy, the lucky applicant happy, the newspaper and its readers were happy (since the insertion cost helped keep down the cover price) and the glass fish found a welcoming new home. It would, in other words, have been wasteful not to have advertised. Exchange & Mart has been eliminating waste since 1868. These days we call it recycling.

Advertising, of itself, can do absolutely nothing (except contribute revenue to its carriers). Advertisements, in theory, can do practically anything: introduce the new, confirm the values of the old, congratulate existing buyers/users/consumers/employees/voters or attempt to convert them to different ways. Advertisements can, and do, encourage expenditure and encourage thrift; and advocate a vote for any number of competing brands, companies or political parties.

Commercial advertisers (manufacturers and retailers, banks and other financial institutions) made up 73 per cent of total 1990 UK recorded advertising expenditure. And the remaining 27 per cent came from classified: property, situations vacant, cars and Lalique glass fishes. Millions of different needs, objectives and decisions make up the grand total – but each item of advertising expenditure, in each of many advertising media, is hoping to see a return on its investment cost.

The motives and objectives of commercial advertisers are sometimes as simple as those of the classified advertiser – to effect sale – but are usually more complex. Consistent advertising can both create and maintain a reputation for consumer brands that can help sell them now, protect their profit margins and safeguard their future from competition. Brand and company reputations tend to decay unless they are constantly tended and conserved.

Furthermore, markets and consumers are not static. All the time, children are growing into young people, young people are getting married and having families, older people are retiring, retired people are dying. At the same time, in almost all markets, there is competition: from old and new competitors, from home and abroad; all of them using advertising – advertisements – to put a case for the opposition. So, simultaneously, some advertisers are using advertisements to attempt to keep their established brands young and relevant and others are using advertisements to make the very same public aware of new choices and developments.

Because of the greater complexity of their aims, the cost effectiveness of many commercial advertising campaigns is a great deal more difficult to establish than for classified advertising. Volume sales cam be measured more accurately than relative price (which may be the more important objective) and long-term values are almost impossible to track. (I know a man who, when he was fifty, bought an Aston Martin. He bought it because of an advertisement he’d read when he was fourteen.)

There are those who believe that television encourages violence. But television, like advertising, is no more than an available channel for communication: there are cameras, transmitters and receivers. And how can these inanimate pieces of hardware, in themselves, conceivably encourage violence? (Except, of course, by declining to function.)

It’s both legitimate and necessary to debate the effect of specified programmes – just as it is to debate the effect of specified advertisements. But to suggest that advertising does this or television does that remains lazy and unhelpful.

One of the few commercially available channels of communication not to suffer from this confusion between the container and the thing it contained is the telephone system. Some subscribers use the telephone to sell insurance policies; some to call the plumber; some to say thank you; some to reach the Samaritans; some to arrange a collection of a consignment of hard drugs; some to listen to Dirty Housewives; some to find out how a birthday went; and some for breathing down and saying knickers. Again, the same available channel of communication is being used for an infinite number of different purposes – including, sadly but inevitably, some abuse. But – presumably because each telephone message is a discrete transmission – no-one has been tempted to debate the effect of the telephone on society on the strength of an arbitrary selection of some of its uses.

The distinction between advertising and advertisements should be clear. It’s been made before by many people. Yet it still seems to be forgotten when the debate hots up. If this series of papers stimulates that debate, let’s hope that the distinction won’t get forgotten this time.